Giro Recap

Today marked the end of the Giro d’Italia, and what a spectacular edition it turned out to be. In what was supposed to be a showdown of Chris Froome and Tom Dumoulin, for the most part looked like anything but, as Simon Yates took the race by storm early on and looked unbeatable up until the end. Froome, having crashed while performing a recon ride of the stage 1 time trial, didn’t show any signs that he would be a factor in the race, slowly bleeding time at various points, though somewhere staying close enough in striking distance. Dumoulin on the other hand, provided a very steady performance, but also seemed incapable of matching Yates in the mountains. Going into stage 18, the race looked pretty much over: Yates had a narrow 28” lead over Dumoulin, but the there consecutive mountain stages didn’t appear to offer any advantage to Dumoulin. Froome seemed to be too far down in the standings with a gap of over 3 minutes behind Yates, and many including myself had earlier questioned whether it was even a good idea for him to stay in the race with his looming participation in the more important Tour de France beginning only a month after the end of the Giro.

Over the last couple of stages, Froome needed a miracle, and on stage 19, he got just that. Attacking up the Colle delle Finestre, a beastly 17.9 km climb averaging 9% including large portions of dirt, Froome managed to distance his rivals and ride solo for the next 80 km or so to the finish, taking over 3 minutes over the closest rivals, notably Dumoulin, with Yates having completely cracked on the very early slopes of the Finestre. To attack that far out is extraordarily ballsy, conjuring up images of Floyd Landis attacking off the front to gain massive time on stage 17 of the 2006 Tour de France, thereby retaking the Maillot Jaune and immediately testing postive for performance enhancing drugs. Competitors, media, and fans alike all let out a collective groan at Froome’s miraculous performance, particularly given that he hadn’t shown much form up until that part of the race and his lingering Salbutamol case.

There’s no doubt that Froome’s performance necessitates scrutiny, but at the same time upon more careful analysis of the actual bike racing, his performance on stage 19 was more about opportunity than raw strength, though not to be mistaken, there was a lot of the latter. With most of the favorites utterly exhausted from a grueling race, Froome, who had declared his intention to build form through the race, appeared to have more left in the tank in the later stages. While the likes of Yates, Dumoulin, and Thibaut Pinot were holding on for survival, Froome was gaining in ability, and launched his attacks (basically telegraphing his plans before the stage) when his competitors simply didn’t have much left in the tank. As noted, Yates had already been in the process of cracking after the stage 16 time trial, and Dumoulin, himself not showing his top form through the race, simply could not match Froome. The most important consideration however, is that after Froome attacked, effectively all of the main contenders were isolated midway up the Finestre, and so it was mano-a-mano until the finish line. While it’s easy to say Froome put in a super human performance, he gained a lot of time on the descents, when the likes of Dumoulin and Pinot chose to wait for Pinot’s teammate, only for Dumoulin to be stuck being the only one willing to chase.

Below I’ll analyze Froome’s and the other contenders performances, notably up the Finestre, but if I had to draw conclusions on the race I witnessed, I’d give Froome and Sky credit for a brilliant move, and place blame on Dumoulin for not following or taking matters into his own hands earlier. Had he followed Froome and not waited for or relied on others to help, he likely would’ve been able to manage his losses a lot better. At 80 km to go though, he hesitated and doubted, and in the end that came back to bite him. Froome did look superb on the bike over those last 80 kilometers of the stage, but as I’ll show below, I calculate that he only did 398 W good for 5.86 W/kg over the roughly 1:04:00 it took him to ascend the Finestre. Note that use of the word only, which while for most mortals reading this blog is a number we can only dream of, but is notably lower than the 6.06 W/kg I calculated Yates did earlier in the race. That 5.86 W/kg during the second to last day in the mountains is a remarkable number, when everyone is hanging on just trying to get to Rome, but the ability to hit those numbers during the end is what it takes to get to the top step of the podium.

I can’t say for certain whether Froome cheated in some way to get that 5.86 W/kg this late in the race, but as I mentioned I feel like tactics played as large a role as anything. The likes of Yates peaked earlier, and it came back to haunt: Yates didn’t get popped after a hard battle on stage 19, he cracked immediately. He didn’t have it and he was found out. Dumoulin never showed top form: he was solid throughout the race, but aside from the time trials his strategy in the mountains was simply to avoid losing time.

I’d also be remiss if I didn’t also analyze stage 14’s Zoncolan climb, which I’ll do below, and of which Froome won in resurgent fashion. Up Zoncolan, Froome completed the climb with a time of 34:20, 8” seconds head of Simon Yates and 37” seconds ahead of Dumoulin, at an estimated 427 W and 6.29 W/kg.

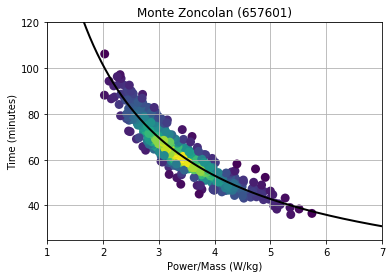

Stage 14: Monte Zoncolan

Let’s begin with stage 14’s Monte Zoncolan, which averages a mind boggling 13% average gradient over 7.5 km. Watching this climb was like watching a bike race in slow motion: the main strategy for the riders was the get the line with maximal individual effort while not cracking. Cracking on this climb would’ve been a kiss of death to any of the main contenders, as there’s almost on way to ascend Zoncolan without pouring power into the pedals. Froome did put in a little dig that managed to get him some distance on Dumoulin and Yates, which turned out to be the move of the day. The attack was somewhat surprising from Froome, considering his prior performances, but given the caliber of rider he is, it wasn’t too far fetched that he could take the stage from Yates by a scant 8 seconds.

In analyzing the data for the climb via the Monte Zoncolan Strava segment in which riders logged their times with an actual power meter and list their masses, as described in my earlier entries, we see the following relationship between average power-to-mass for the climb with the time to complete the climb. The relationship can be modeled mathematically to give the following equation:

<power>/mass = (13351 W/kg*s)/(time (s)) + (-0.19580 W/kg)

<power>/mass = (13351 W/kg*s)/(time (s)) + (-0.19580 W/kg)

where <power> denotes average power during the segment. The top time on the Strava segment belongs to Pinot at 35:02, who officially finished 42 seconds behind Froome on the day. From this, we can infer Froome finished with a time of 34:20, at an estimated 427 W (or 6.29 W/kg). Yates, with a time of 34:28, did an estimated 6.26 W/kg good for 373 W, while Dumoulin finishing at 34:57 with an estimated 6.17 W/kg, 438 W performance. These values are certainly larger than we saw, particularly from Yates on Montevergine, where I estimated his output at 6.06 W/kg. Given the steepness of this climb, I would actually expect accuracy of the model to be a little bit better, though it is possible that it’s overestimating their performances. On the other hand, some of my personal best power outputs have come on the steepest of gradients (as opposed to flat time trial efforts), so it is plausible the hellish grades of Zoncolan allowed them to fully tap their engines, maximizing power delivered the pedals. At any rate, the estimations were consistent across the top riders, and any questions are more around how Froome managed to record this performance after a lackluster showcasing before that. Also of note, and as I’ll document here in the coming days, is I calculated a similar performance for Egan Bernal during the Gibraltar climb of this year’s Tour of California. So perhaps these are levels that we can note from cyclists with top form, and the earlier days were more indicative that we hadn’t seen an elite performance.

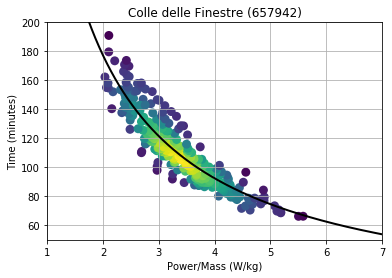

Stage 19: Colle delle Finestre

Having provided commentary above, let’s just get straight to business here. Froome summitted the climb about 45 seconds ahead of Pinot (and Dumoulin) on the Finestre, the latter two of whom completed the climb in 1:04:45. That put Froome at 398 W for 5.86 W/kg, and Dumoulin/Pinot at 5.79 W/kg. These aren’t crazy numbers, who are fairly audacious considering 80 km to go. Froome’s performance up the Finestre wasn’t in itself transcendant, as much as his ability to stay away for the next 80 km. As I mentioned above though, a large part of this is that we saw effectively Froome vs. Dumoulin, mano-a-mano on an entirely mountainous stage, and not Froome vs. peloton on a flat stage, of which would’ve made this performance absolutely unbelievable to me.

Below you can find the data from the Colle delle Finestre segment, along with the model shown in the figure and given in mathematical form.

<power>/mass = (23181 W/kg*s)/(time (s)) + (-0.17987 W/kg)

<power>/mass = (23181 W/kg*s)/(time (s)) + (-0.17987 W/kg)

It should be noted that Froome’s time is less than Steven Kruijswijk’s time from the 2016 Giro d’Italia by about 17 seconds, though during that edition the Finestre was a summit finish, for which we could’ve expected more of an all-out effort.

Discussion

When I first wrote about Froome regarding his performance on Stage 10 of the 2015 Tour de France, I felt that given my calculations and his background, we owed him the benefit of the doubt. Now? I’m not so sure. Did he gain an advantage from over doing it on the Salbutamol inhaler? Perhaps. Should we be skeptical of Team Sky given Bradley Wiggins’ hypocritical cortisone injections? Absolutely. Can we conclude that Team Sky and Froome are full of it, and are just as dirty as we’ve seen in the past? Who knows. I’m inclined to believe Froome’s and the peloton’s performances are largely legitimate these days, or maybe it’s just me hoping optimistically that cycling has turned the corner. Either way, it’s hard to say. What I can say is that I do largely believe in the methodology I’ve developed in estimating power-to-mass performances given times on climbs, and I haven’t seen anything that’s made me jump out of my seat. The likes of Froome can’t hide from physics, data, and statistics, of which my model is built upon, and nothing on this end has screamed suspicious to me. If there is something I could point to, it’d be to Froome’s remarkable return of form during the race, but perhaps their plan to race into form worked after all, or perhaps they were using something to help Froome recover better. It’s just really hard to say, and I’d feel irresponsible to speculate affirmatively based on what I’ve seen.

If I had to guess, I’d guess Froome raced clean and won the race as a result of coming into form as others were melting, as well as brilliant tactics on stage 19, of which we’ve seen recently from Quintana during his 2016 Vuelta victory (over Froome no less), or Contador’s long range attack in the 2012 Vuelta to grab the leader’s jersey from Joaquim Rodriguez. He did just enough early on to hang on, and then seized the moment with just enough time. Still, Froome and Sky through way of Salbutamol and Cortisone have lost the benefit of the doubt, and we should scrutinize them much more now than ever.

What’s next? Stay tuned for a long overdue analysis of the Tour of California, in which we saw the affirmation of the massive talent that is Bernal. I’ll post analysis of the Gibraltar and Kingsbury climbs, and then after that perhaps I’ll post about the Criterium de Dauphine or Tour de Suisse ahead of the Tour de France. This year’s Tour is shaping up to be very promising, as we’ll see a fresh Nairo Quintana, Romain Bardet, and Vincenzo Nibali take on an assuredly fatigued Froome and Dumoulin. I’m also particularly excited to see Bernal make his Tour debut in support of Froome. After his Tour of California performance and with Froome having been struggling in the Giro at that moment, Sky realized that he’d make for a great insurance policy and support for Froome should he falter given his participation in the Giro.

Stay tuned!