Giro 2018, Montevergine & Gran Sasso

This weekend featured two summit finishes, up the Montevergine and Campo Imperatore (Gran Sasso) on Saturday and Sunday, respectively. As I expected, the Montevergine proved to be a non-factor in the battle for the overall, save for the young Ecuadorian Movistar rider, Ricard Carapaz jumping out of the pack late in climb to take 7 seconds over his competitors. At 5%, Montevergine is more of a power climb, where the big riders aren’t as hampered by their larger weight as their power counts for more, and moreover aerodynamics becoming a non-negligible factor provided the climbing speed is high enough, which it turned out to be on a relatively easy gradient.

Today’s climb up Campo Imperatore in the Gran Sasso range proved to be more exciting, with a ever increasing gradient towards the line. Simon Yates further demonstrated his excellent form by taking the victory ahead of Thibaut Pinot and teammate Esteban Chaves, to further gain time on pre-race favorites Tom Dumoulin (12”) and Chris Froome (1’07”), the latter of whom who got dropped withover 2 km to go. At this point, perhaps the more interesting plot-line regarding Froome is if/when Team Sky will pull the plug on their Giro ambitions, and allow Froome time to rest and recover ahead of the Tour de France, as it appears even a podium spot at this point is out of the question.

Perhaps intriguing is the level of performance we have seen out of the traditional group of climbers, Yates, Pinot, Chavez, and Pozzovivo, all of whom put in relatively strong performances in the opening time trial and have maintained form through the first 9 stages. Yates maintains he believes he’ll need minutes over Dumoulin to feel safe with his lead before the flat 34.2 km time trial on stage 16, and it is fairly likely he or another of the aforementioned climbers will be able to manage to pull more time on Dumoulin on Zoncolan, given the sharp profile of the climb.

What does this all mean? This is going to be a wide open Giro, and the winner will have certainly earned it. With that said, let’s take a look at the Strava data from this weekend’s two summit finishes, as well as estimate the performance of key riders on the climbs. For reference, an over of the climbs is given in one of my entries from last week.

Montevergine

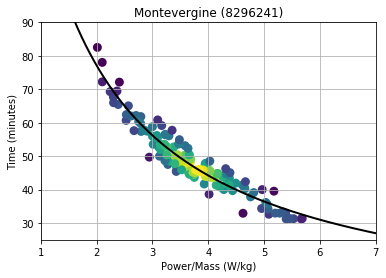

Though long at 14.8 km, Montevergine (Strava segment) proved not to be steep enough for the leaders to separate themselves, with a pack finish amongst the favorites. With that said, let’s still take a look to see how time of completion maps to average power-to-mass over the climb to get an idea of their performances. As described in my Giro climb summary entry, power-to-mass for a rider up Montevergine can be described by their completion time given the equation

<power>/mass = (14047 W/kg*s)/(time in seconds) + (-1.1574 W/kg)

[editor’s note: working on MathJax fix]

which is shown inverted in the following figure, as fit to Strava data using only results recorded with a power meter.

The results of this equation applied to the favorites is shown in the table below.

| Place | Name | Stage time | Strava time | Est. time | Est. W/kg | mass (kg) | Est. power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Richard Carapaz | 5:11:35 | 31:03 | 5.99 | 62 | 371 | |

| 3 | Thibaut Pinot | +7” | 31:10 | 5.97 | 65 | 387 | |

| 5 | Simon Yates | s.t. | 31:10 | 5.97 | 59.65 | 355 | |

| 6 | Domenico Pozzivivo | s.t. | 31:11 | 5.97 | 53 | 316 | |

| 7 | Esteban Chavez | s.t. | 31:11 | 5.96 | 55 | 327 | |

| 9 | Mike Woods | s.t. | 31:11 | 5.96 | 63 | 375 | |

| 11 | Tom Dumoulin | s.t. | 31:12 | 5.96 | 71 | 423 | |

| 13 | Rohan Dennis | s.t. | 31:12 | 5.96 | 71 | 423 | |

| 14 | Miguel Angel Lopez | s.t. | 31:13 | 5.96 | 65 | 387 | |

| 15 | George Bennett | s.t. | 31:14 | 5.95 | 58 | 345 | |

| 20 | Fabio Aru | s.t. | 31:15 | 5.95 | 66 | 392 | |

| 22 | Chris Froome | s.t. | 31:15 | 5.95 | 68 | 404 |

It’s pretty amazing to see the power outputs were effectively the same as Etna, with the performances just about at 6 W/kg. I wouldn’t be surprised if these numbers were just a tiny bit lower in reality, since the climb today probably offered a small amount of drafting. Still, it’s amazing to see the consistency of threshold efforts across different climbs, and the level these athletes are at during this edition of the Giro. At this point, it’s almost a game of who can repeat this performance over the course of the race, as any rider is prone to having a bad day on any particular day. Also amazing to see is the discrepancy in powers across the riders, given their differences in mass. Pozzovivo needed only 316 W to keep up, whereas Dumoulin and Dennis pushed out a massive 423 W, and it’s differences like these why we see the likes of the latter two much more dominant in the long, flat time trials, where raw power counts for so much more.

Campo Imperatore (Gran Sasso)

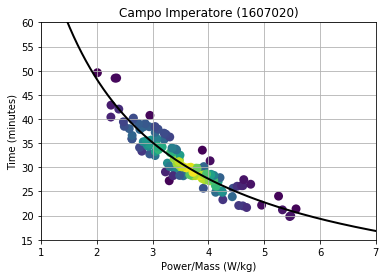

Gran Sasso turned out to be a decisive climb as noted above, Yates was able claw time over other favorites, notable Dumoulin and Froome, the latter of whom last over a minute in the finale. Though the climb is longer than the Strava segment I’ve chosen to analyze, I think it’s more instructive to study the last section, as there is a relative lull in the longer segment. To study the efforts on this climb by fitting the Strava data to our representative climb equation, we obtain

<power>/mass = (7752.3 W/kg*s)/(time in seconds) + (-0.67723 W/kg)

[editor’s note: working on MathJax fix]

which is shown inverted in the following figure, as fit to Strava data using only results recorded with a power meter.

The results of this equation applied to the favorites is shown in the table below.

| Place | Name | Stage time | Strava time | Est. time | Est. W/kg | mass (kg) | Est. power (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simon Yates | 5:54:13 | 19:24 | 5.98 | 59.65 | 356 | |

| 2 | Thibaut Pinot | s.t. | 19:25 | 5.98 | 65 | 388 | |

| 3 | Esteban Chavez | s.t. | 19:25 | 5.98 | 55 | 328 | |

| 4 | Domenico Pozzivivo | +4” | 19:29 | 5.97 | 53 | 315 | |

| 5 | Richard Carapaz | s.t. | 19:30 | 5.95 | 62 | 368 | |

| 7 | George Bennett | +12” | 19:41 | 5.89 | 58 | 341 | |

| 8 | Tom Dumoulin | s.t. | 19:42 | 5.88 | 71 | 417 | |

| 9 | Miguel Angel Lopez | s.t. | 19:43 | 5.88 | 65 | 381 | |

| 12 | Mike Woods | +36” | 19:59 | 5.79 | 63 | 364 | |

| 21 | Rohan Dennis | +1’02” | 20:26 | 5.65 | 71 | 400 | |

| 23 | Chris Froome | +1’07” | 20:31 | 5.62 | 68 | 382 | |

| 24 | Fabio Aru | +1’14” | 20:38 | 5.58 | 66 | 368 |

Wow. It’s incredible to see the consistency of performance from climb-to-climb, with the day’s first finisher always coming in right around 6 W/kg. Unlike the previous couple of climbs, Etna and Montevergine, in which all of the main contenders finished in the 5.9-6 W/kg range (except for Yates’ incredible 6.06 W/kg Etna performance), Campo Imperatore was the first day in which riders were found out. Yates, the winner on the day, came in at 5.98 W/kg, consistent with the other performance, yet the big losers on the day, notably Froome, verifiably cracked. Froome, who had outputted dual performances at about 405 W (about 10 W less than his notable performances at the Tour de France), only mustered 382 W today.

The big takeaway from today’s performances is that top end form isn’t enough, rather it’s consistency with top form that makes a grand tour champion. One bad day and you could very well have sacrificed your chances at the podium. While Yates has been remarkable, his performances haven’t separated him all that much from the other contenders in terms of power-to-mass. Rather, maybe he had one really good day, but he’s just been consistent at that top level thus far. Froome on the other hand, got found out. He didn’t have it, perhaps for a lack of training, perhaps from stress via the media surrounding his legal case, or perhaps simply just a bad day. Either way, at 5.62 W/kg, there’s no hiding he wasn’t dropped by an extraordinary performance, rather, he may not be in the condition we’ve come to know him during July.

Moreover, it’s particularly gratifying to see results around 6 W/kg. Sure, you could argue this isn’t the Tour de France so perhaps this isn’t the cream of the crop, at least in terms of conditioning, but these are some of the perennial favorites, and they aren’t producing values that we see in the Lance Armstrong era, which were approaching 7 W/kg. As a physicist and machine learning specialist, admittedly there is some wiggle room in these values, but in practice I’ve found them to be quite small, about 1% (+/- 5 W) or so at most. The equation is based off of physics calculations I’ve done, and instead of estimating hard-to-estimate parameters such as friction, cross-sectional area, and wind speed, I simply infer them by fitting my derived equation to actual data.

Next up we have Monte Zoncolan on stage 14, and in my eyes promises to be the one of the two defining moments of this Giro, along with the time trial on stage 16. The climbers need to distance the likes of Dumoulin (let alone each other) to have a real chance at the title, Dumoulin has the ability to take minutes from them. At an absolutely brutal average gradient of 13%, Zoncolan will absolutely favor climbers with smaller weights, and my guess is that Dumoulin will lose around a minute to the likes of Yates, who I might expect to take the day given his form and his very slight stature. The real question is if a lead of 1-2 minutes will be enough to stay away in the time trial, as the climbs during the last week aren’t formidable enough to offer a decisive advantage to the pure climbers. Either way, this should make for a close battle heading into Rome, and I’ll be posting more updates along the way!